Place-Time-Play: contemporary art from the West Heavens to the Middle Kingdom

Place-Time-Playwill mark the first major engagement between contemporary artists from India (historically referred to as the West Heavens in Chinese and Japanese Buddhist texts) and China (referred to as Zhong Guoor Middle Kingdom in Chinese language). Under the aegis of the Visual Culture Research Institute of the China Art Academy, Hangzhou, this project includes a major art exhibition and a series of intellectual forums to take place in Shanghai. This project builds on a series of investigations into the internal boundaries of Asia, and follows upon two previous projects Edges of the Earth: Migration of Asian Art and Regional Politics, An Investigative Journey in Art, a series of research journeys to Asian countries in 2003, and Farewell to Post-Colonialism: Guangzhou Triennial 2008, an exhibition with forums in 2008 that investigated creative possibilities under present predicaments of cultural politics.

Although recent decades have seen an explosion of market-driven interest in the contemporary art of these two “giant” countries, there has been little, if any, interaction between them. Awareness of each other’s art practice is limited to occasional encounters at biennales and art fairs in different parts of the world. To date, there has been no project which specifically involves artists from India and China working alongside each other.

At the conceptual level, the project is conceived as operating at three levels—place, time and play—as signalled in the title. Reckonings with placeimply an understanding of contextual difference, and an attempt to enter another site or location. Taking timeis both a requirement of this process, and an opportunity to encounter a different sense of historical time, and for artists to participate in thinking about and working with the formidable burdens of tradition as well as current economic, political and artistic conditions.

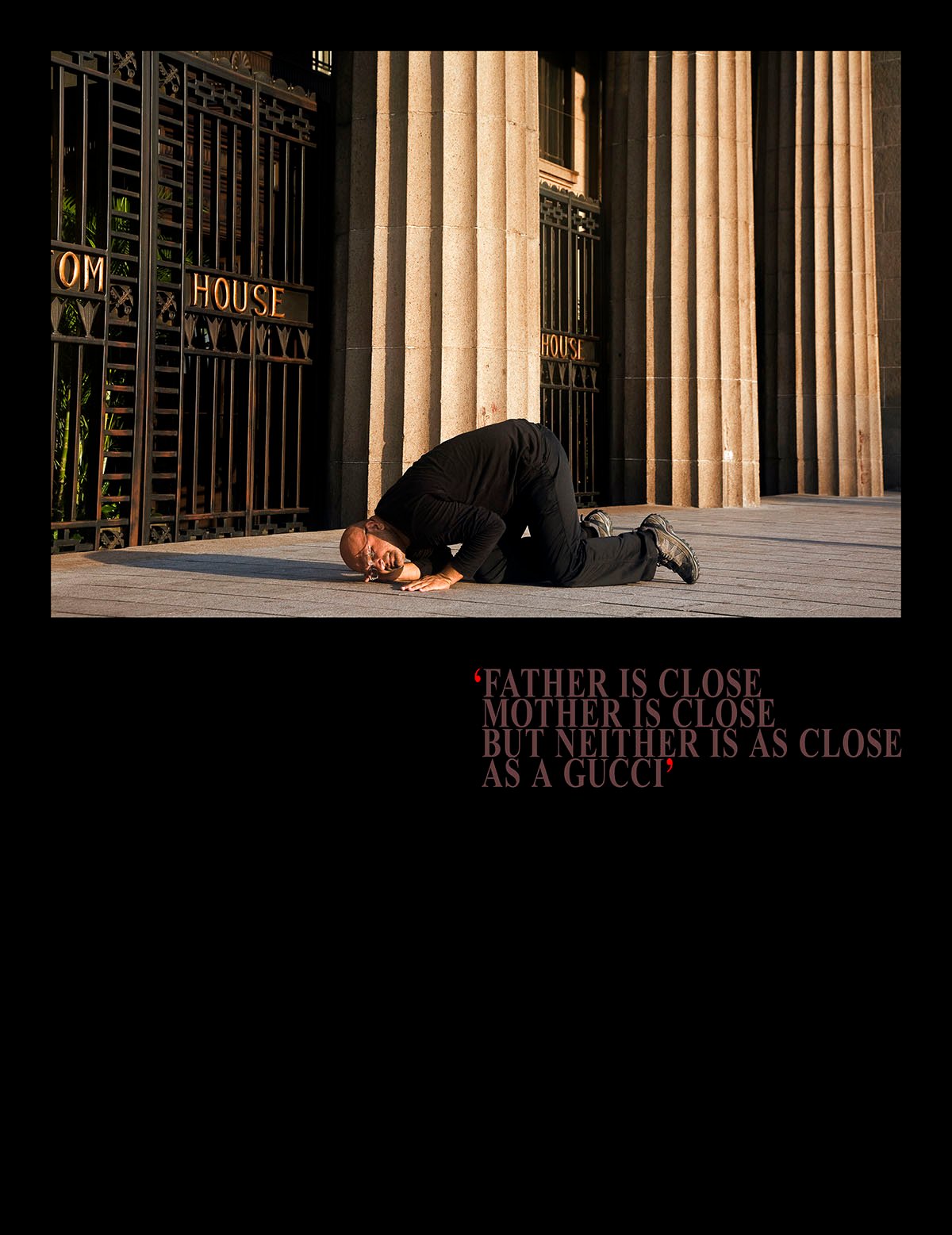

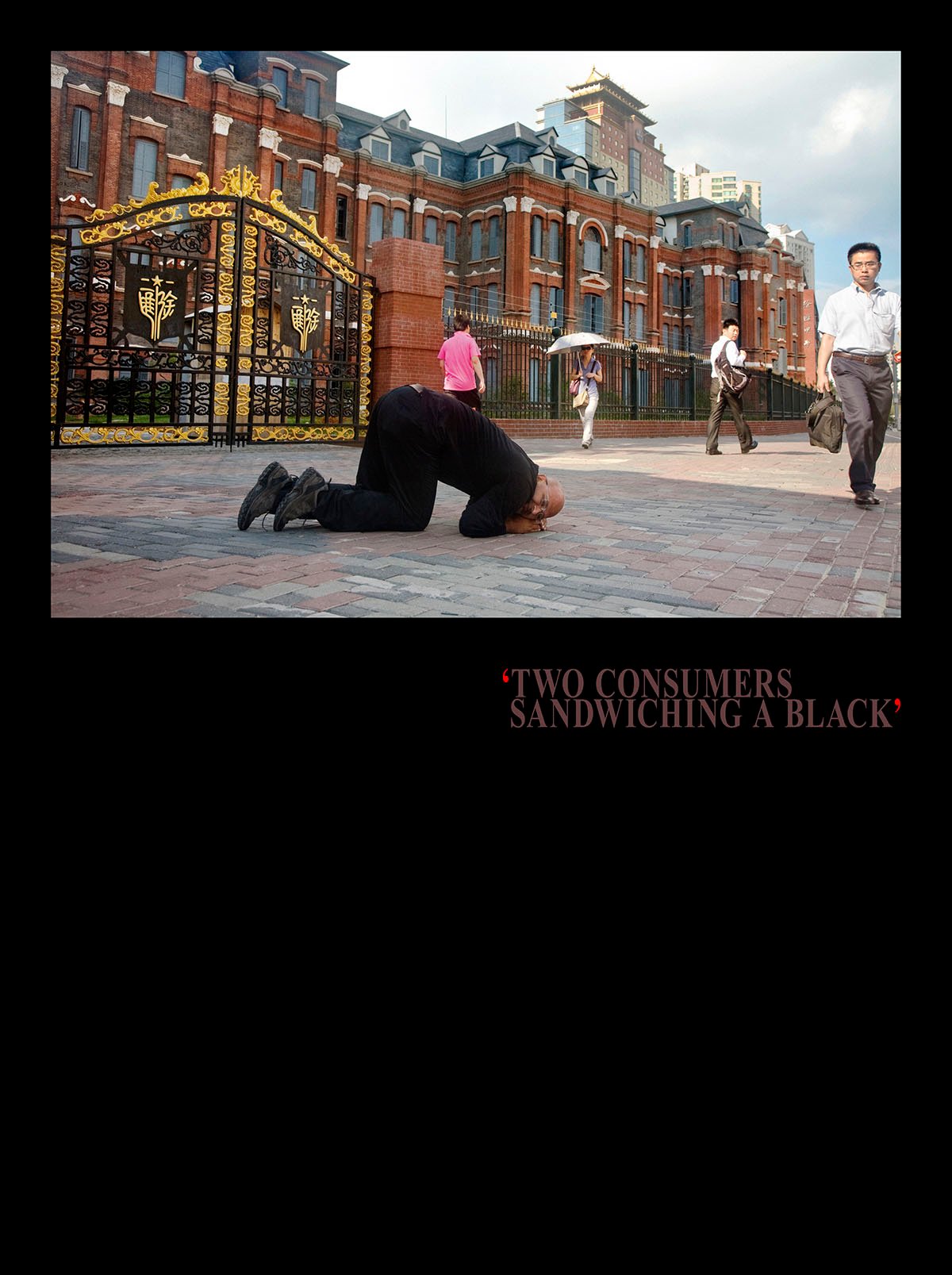

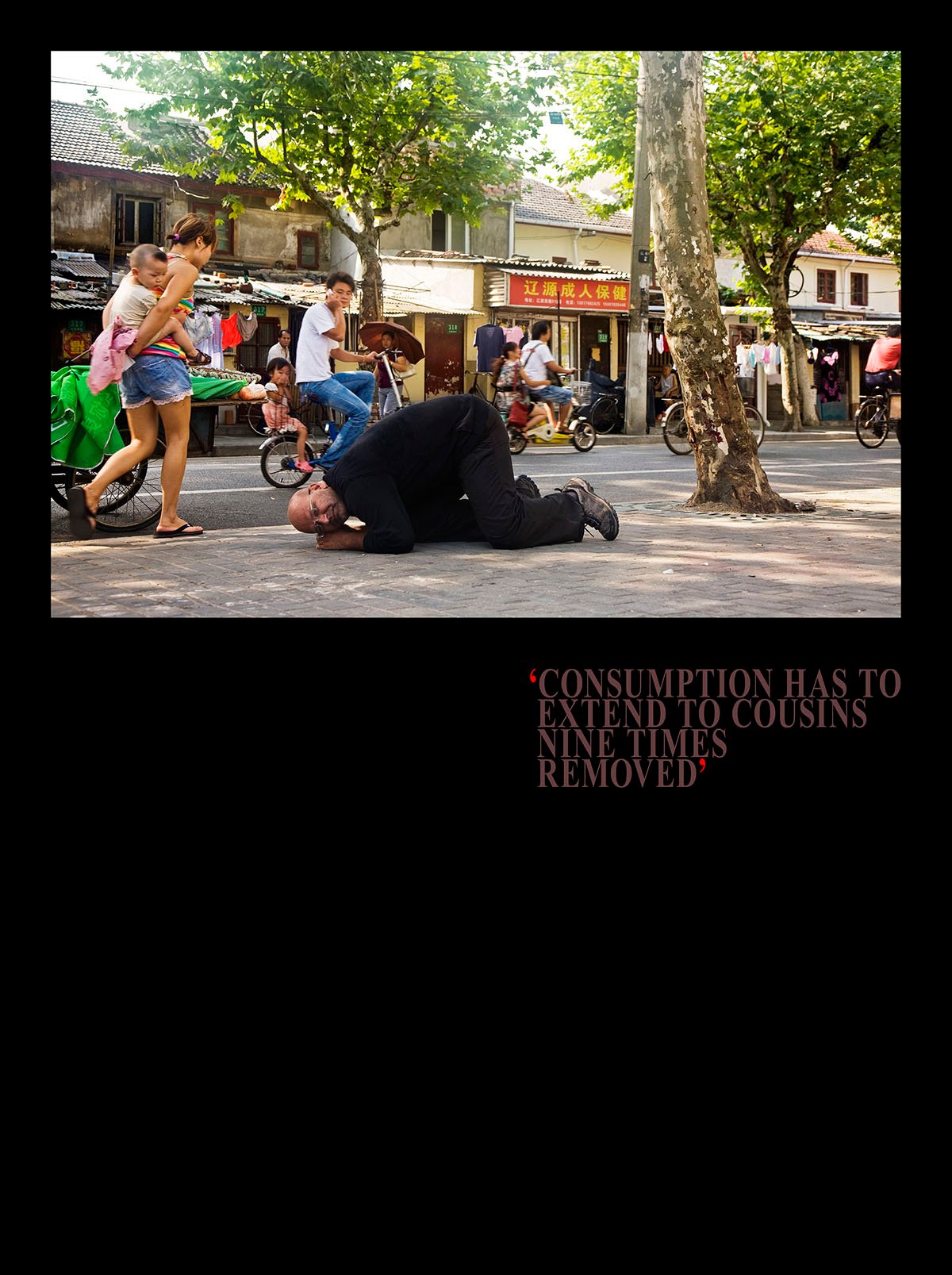

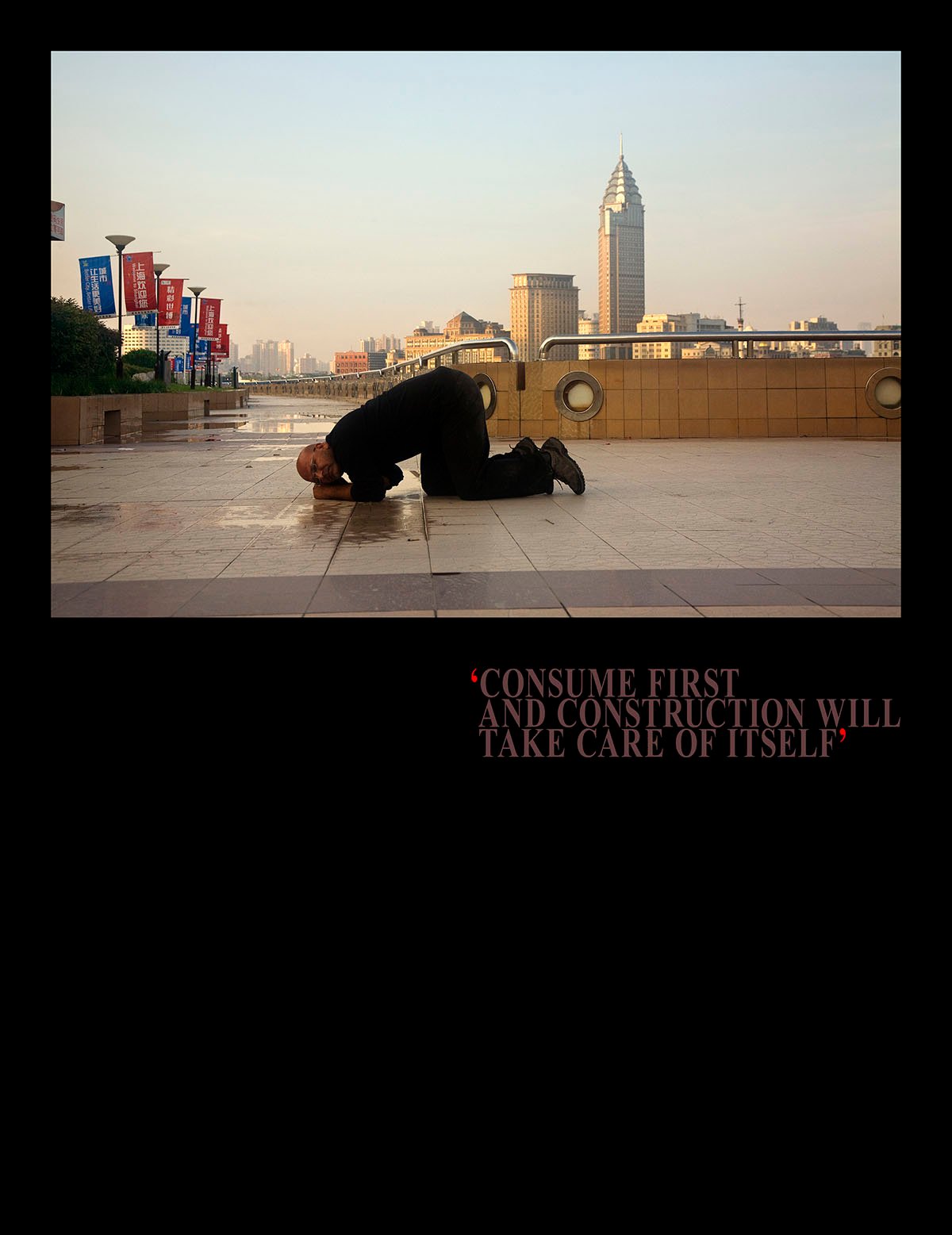

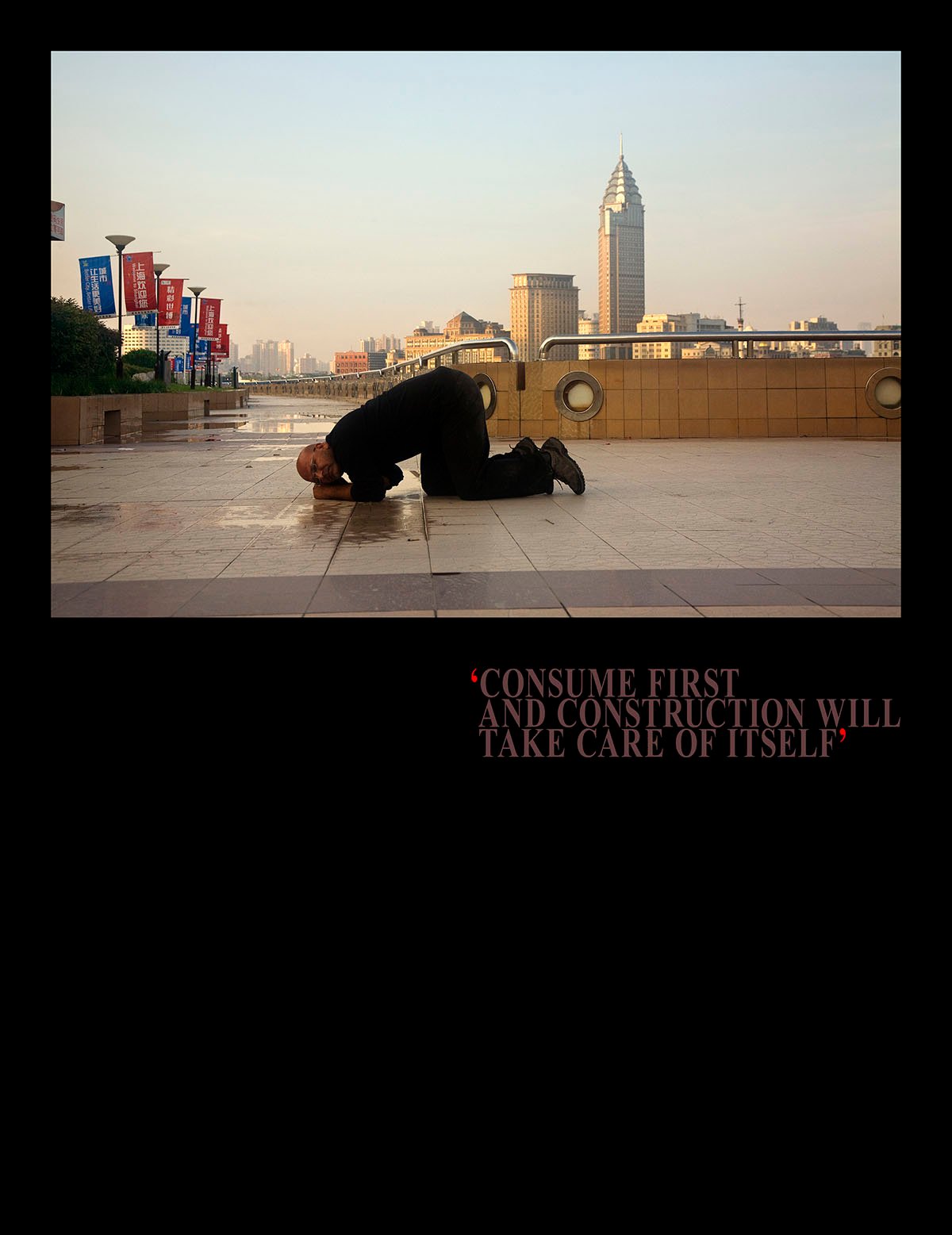

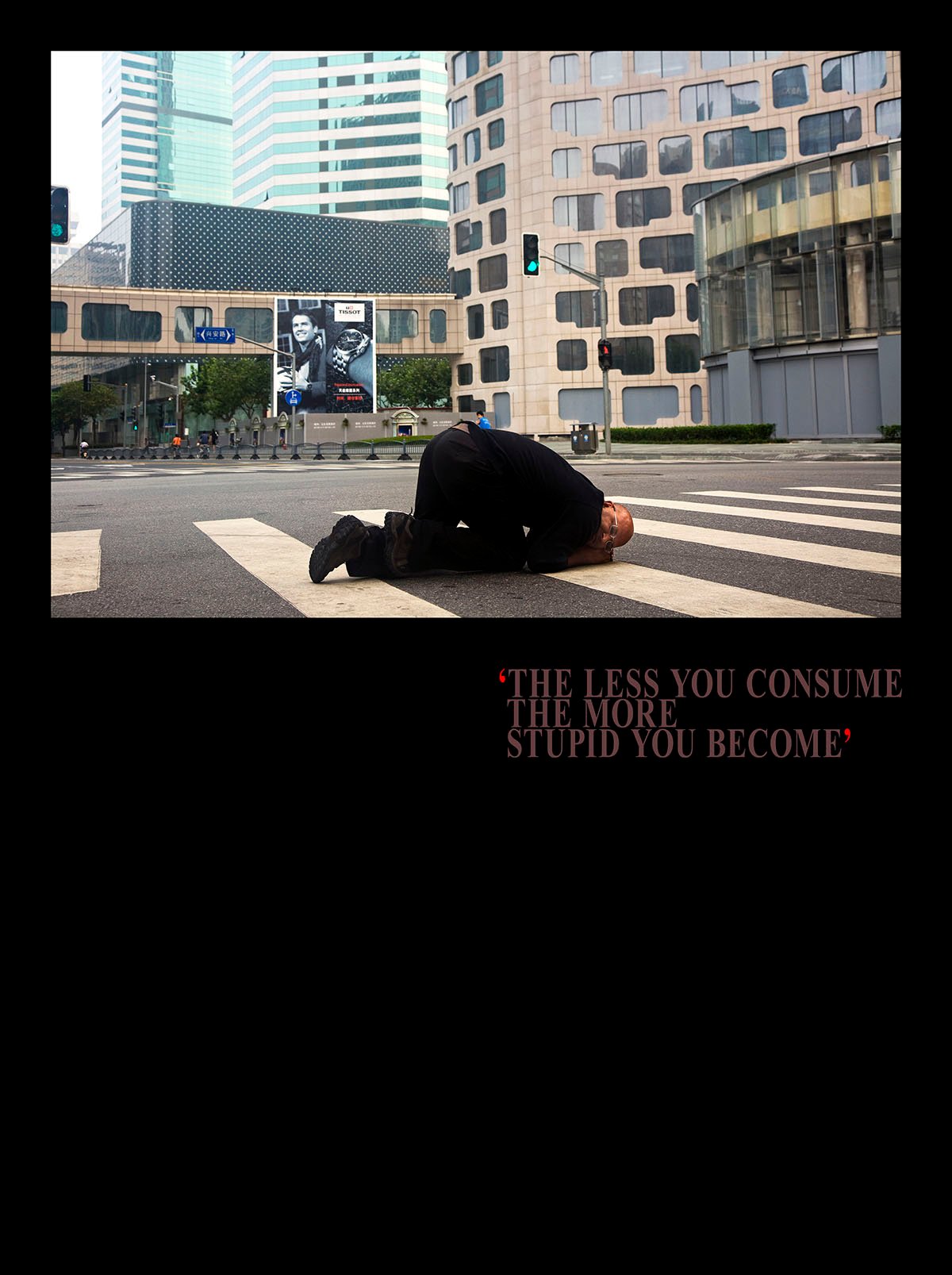

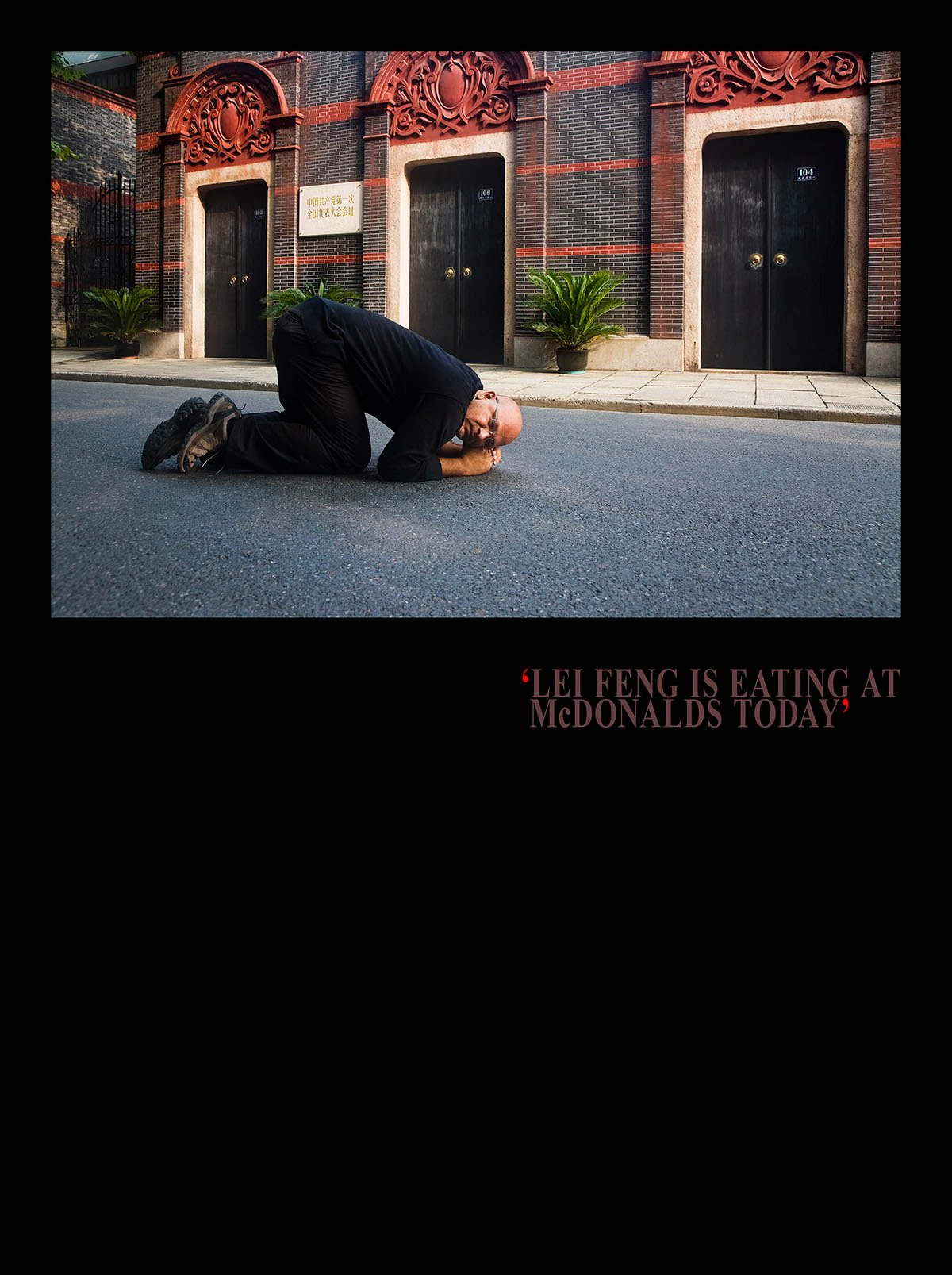

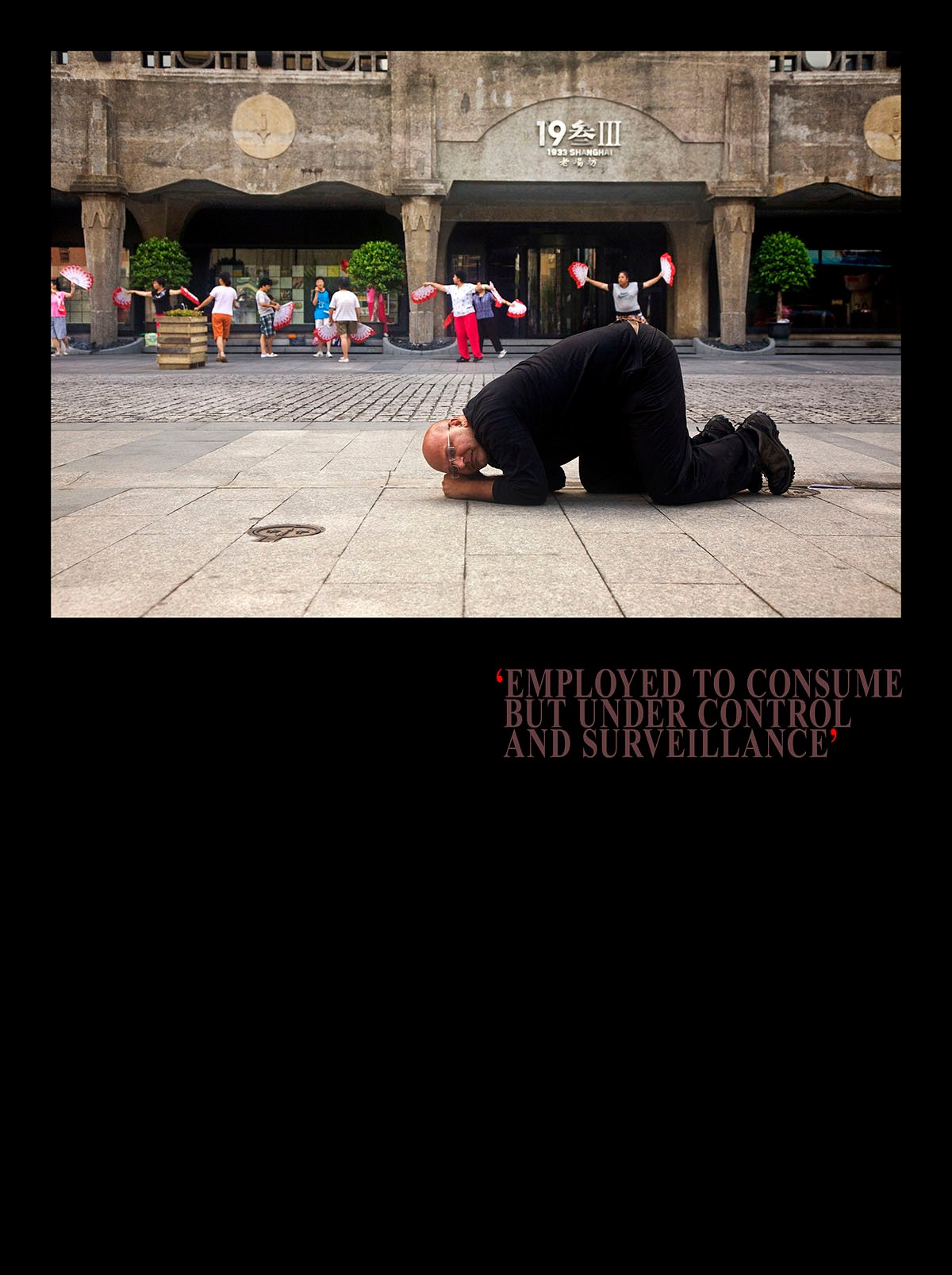

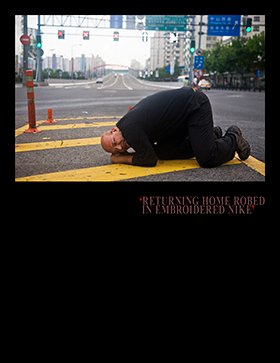

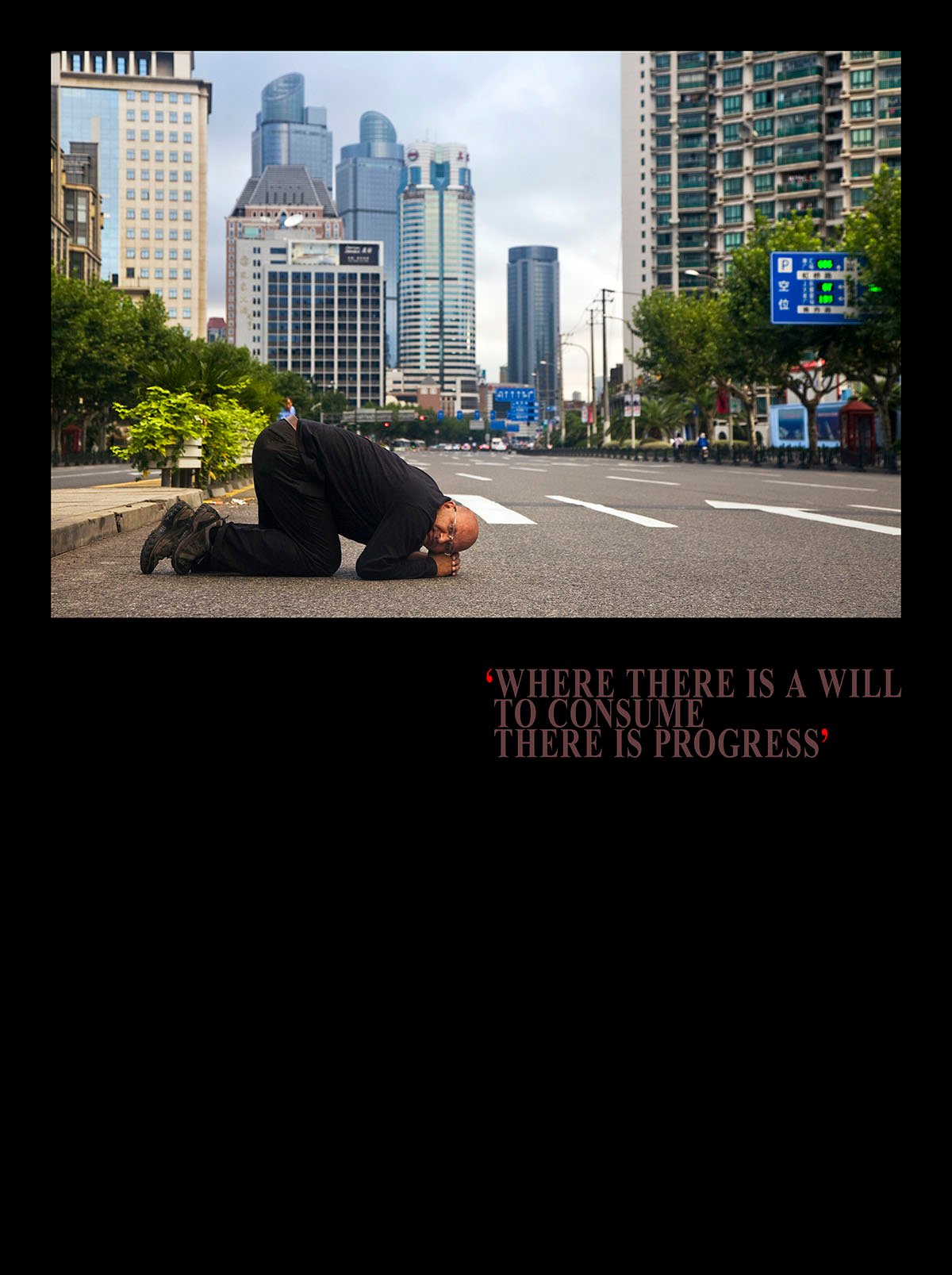

Finally, artists are invited to consider the role of play in contemporary life. The invitation to play is extended on the premise that the idea of imaginative play is a fundamentally life-affirming gesture, too often lost in the quest for topical issues that the art object must address. The fraught nature of diplomatic relations between the two countries has perhaps played the dominant role in governing cultural encounters to date. Through its invitation to indulge in a basic and universal human activity (and need), the project hopes to inaugurate a more lasting series of relationships between artist communities across the two nations.

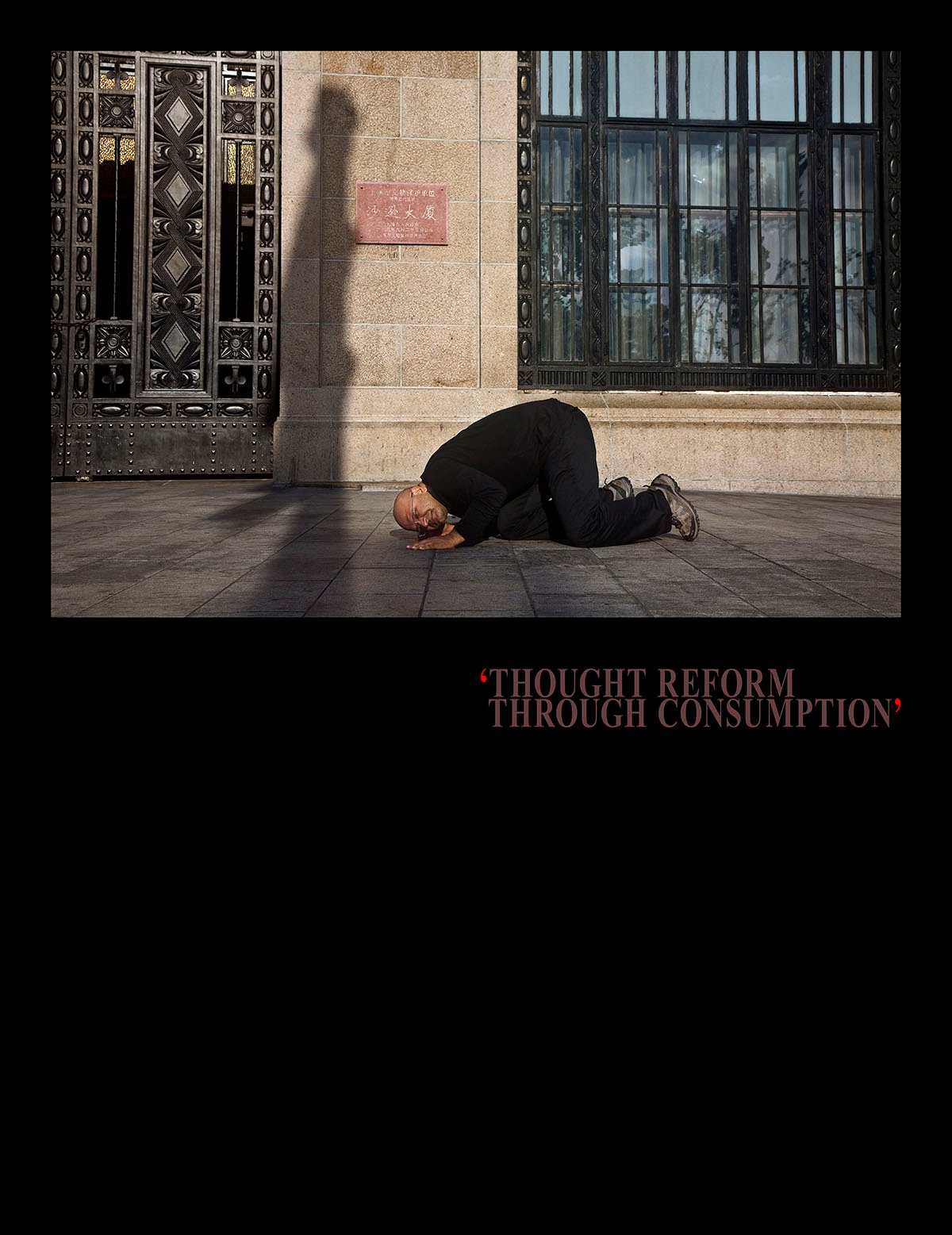

The theoretical underpinnings of the project may be spelled out as Imaginary Orders. In addition to their meaning as commands, ordersin the biological sciences refer to systems of classifications. Especially in view of the nexus between scientific classification, colonial exploration and contemporary notions of division of labour under a globalised economic system, the notion of “ordered” worlds is crucial to a critique of China as the world’s factory, or India as a prime supplier of skilled labour that speaks English. Imaginary Orderssignals an investigation of historical and contemporary notions of classification and belonging, as juxtaposed to trans-local, trans-national imagination as represented by many contemporary artists who find it imperative to question locality and national limits on belonging in their work. It is important to note that historical nomenclatures such as “West Heavens” or “Middle Kingdom” stem from projects of ordering the world, yielding a sense of location, belonging as well as “othering”. As modern nation states, both the Republic of India and the Peoples’ Republic of China are as much projects of the imagination as they are real empires comprising several internal differences and dissensions that both New Delhi and Beijing strive to keep in check. The phantom of unified national culture and its binary relationship with a dominant (Western) international sphere has characterized many aspects of political, technological, cultural and artistic histories in both countries.

After a century of revolutions and reforms, as a “modern” culture China is still strongly under the spell of a bipolar “East/West” mentality. This frame of mind has helped China to see itself through the mirror of the West, but it has also seriously impaired other dimensions of cultural perception. A similar predicament faces India, and several other Asian countries to different degrees. Intra-Asian exchanges are now urgent, both for furthering self-understanding and opening local resources hidden by established discourses. It is also important for strengthening cultural exchanges within Asia. Imaginary Ordersattempts to initiate a meaningful dialogue between China and India, with China as the subject addressed by Indian artistic imagination, and vice-versa.

In the past two decades, cultural studies in the West have been invigorated by the voices of “outsiders”, especially through the work of postcolonial (including Indian) scholars working within the erstwhile strongholds of Euro-American academia. Texts by Indian scholars in post-colonial and visual culture studies have made their influence felt in cultural politics and visual art practices, affecting an entire generation of scholarship. By comparison Chinese academics have not yet made comparable contributions to the world that is worthy of its illustrious history and dramatic revolution. This to a large extent is the result of China’s obsession with the West, which has obscured other perspectives, including creative reading of its own history.

This is a dual project of visual art and intellectual forums. For the academic part we are planning to invite scholars from India and elsewhere to visit China separately, to encourage in-depth exchange with Chinese colleagues. The exchange will hopefully stimulate ideas for joint research efforts in the cultural field.

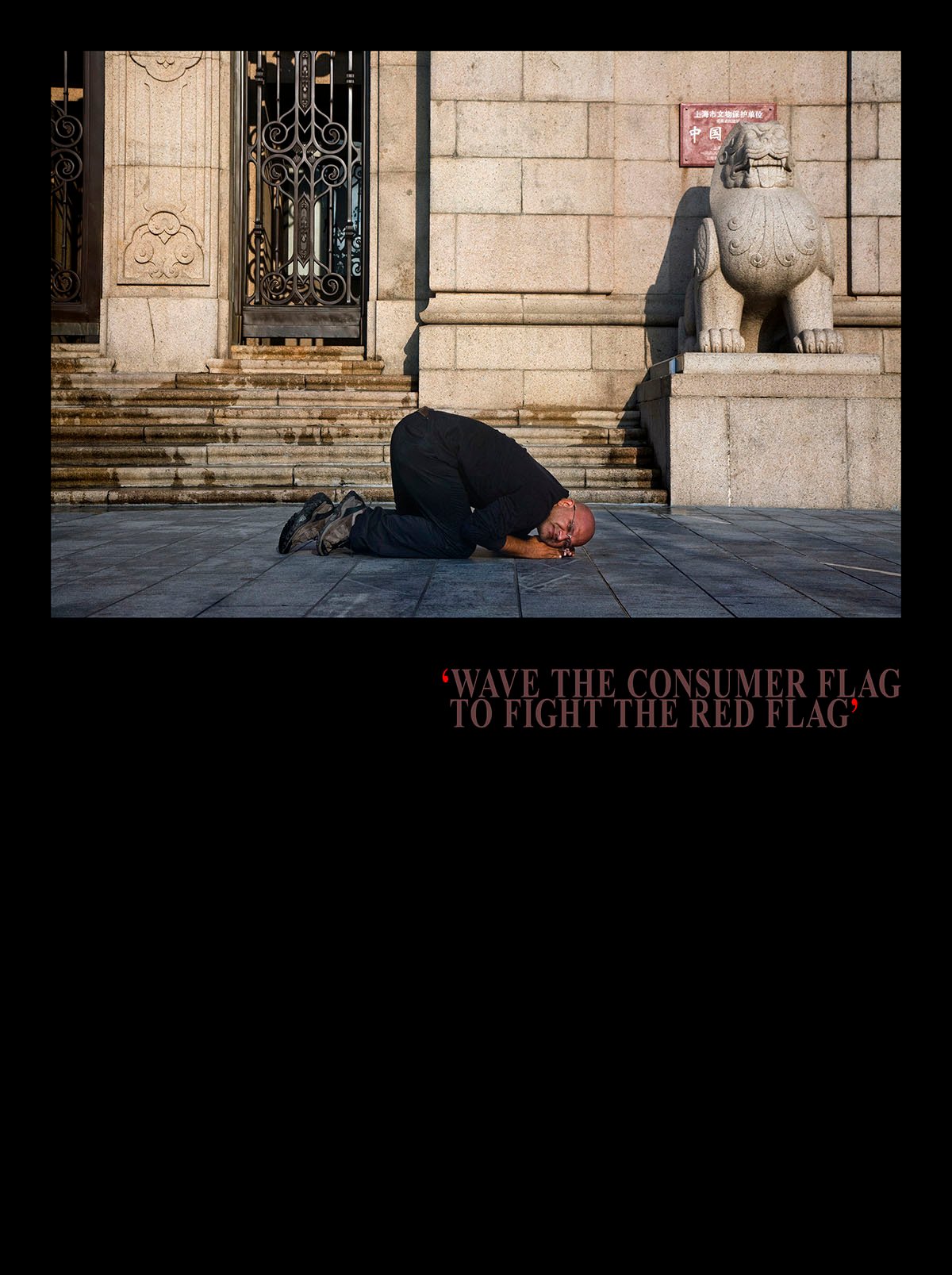

The visual art programme consists of a major exhibition in late October 2010, preceded by reciprocal travel opportunities for artists to research and initiate work. The exhibition will include about 12-15 artists. Until now, internal exhibitions in Asia have mainly meant moving around artworks, which rarely achieve the intended artistic dialogue. Exception to the rule is when Asian artists make works for western exhibitions, when the West is imagined and addressed as the arbitrator of artistic legitimacy. Therefore, we intend this project to be a curatorial experiment. Apart from the practice of exchange residency, the curators expressly urge Indian artists to create work that engages with China as a subject of the imagination, and targeted at the Chinese audience, without the intention of ultimately submitting to the scrutiny of Western platforms. They are asked to treat China as a laboratory for testing new Indian ideas and its modern experience. They should take China as the object of desire or critique, or the subject of cultural reception, and India as the originator of its own unique experience and knowledge. Having stated this intention, we need to add that this exercise is clearly conscious of its references within the arena of contemporary art, and there is no avoiding the main dialect of the dominant western discourse.

We plan to invite about 6-8 Indian artists to China. Artists planning to construct large works can manufacture them here; this not only reduces production costs and trouble of transportation, it also encourages artists to directly engage the proverbial production factory of China. A reciprocal visit of five Chinese artists to India will hopefully add a cross-border perspective.

For more than a century, challenges of imperialism and capitalism have forced India and China to develop strategies that have profoundly transformed both societies. To share this experience is valuable for Indian and Chinese artists alike. For China, long before the seismic cultural shift towards the West it had experienced one other profound cultural turn. The Buddhist turn did not come with comparable destructive fervour as the past century of revolutions, but its influence was just as far reaching; and Buddhist learning took many centuries, from Han dynasty scholars to Song dynasty philosophers, before it was fully absorbed into Confucian scholarship. For China, after a century of revolutions, it is important to remember this history of cultural self-transformation; it is critical to remind ourselves that in our imagination of the world there is not just the West, but also the West Heavens.

Dates:

Exhibition to open in Shanghai in late October 2010; a series of intellectual forums to be held from October to December 2010.

Curators: Chaitanya Sambrani, Chang Tsong-zung, Gao Shiming

Presented by(credits to be confirmed): The Municipal Government of Huangpu District (Shanghai), China Art Academy (Hangzhou)

Organised by: Visual Cultural Research Institute, Hanart TZ Gallery

Venues (exhibition/s and forums)to be confirmed: exhibition site is a renovated warehouse south of the Bund. Forums will be held at universities.